Even after World War II came to an end and Denmark took over the administration of Greenland again, the country remained a more politically open territory than prior to the war. Amongst the Greenlandic people, there were many who wished for Greenland to be (further) modernized. Simultaneously, in the post-war years, the UN made it a mission to call for the decolonization of the world, and going with both these claims, Greenland in the year 1953 ceased to be a colony and gained political status as an amt (somewhat similar to ‘county’) in Denmark (Heinrich 2012: 230-3, 262). In the following decades, there was considerable expansion in the infrastructure in Greenland. At the same time, a number of small settlements and even the mining town of Qullissat were closed down, adding an element of politics to vaigat music that lingers today, since the style is strongly associated with the town and the painful collective memory of its clearance (cf. Johansen 2001: 172; Sørensen 2013). The former inhabitants from these places were distributed across the remaining towns and settlements where it would then be less expensive to offer them modern housing and access to hospitals, schools and communication (Sørensen 1995: 99; Forchhammer 2001). Another factor in this policy was that the growing fishing industry was believed to offer the best opportunities for employment, and the interests of this industry were best served by concentrating the population in fewer towns (Heinrich 2012: 252). During this period, in the Greenlandic school system, measures were taken to make more children competent in the Danish language. The goal was to standardize the quality of the school system and develop opportunities for post-secondary education in Denmark (Gaviria 2013: 62). However, one of the results of these measures, concentration policies and ‘modernization’ was that an increasing number of people saw these changes as a neglect of Greenlandic language and culture, and thus, this historic period is often referred to as ‘the Danification’ (cf. Bjørst 2008: 23-4).

The proclaimed reason for these major changes in Greenlandic society was to ensure that Greenlanders were given equal opportunities to citizens in other parts of the Danish realm (Heinrich 2012: 263-4), but parallel with this development, a law was passed in 1964 known as fødestedskriteriet (‘the birth place criterion’). This law stated that public servants who were from Denmark were given better salary and conditions of employment than public servants who were from Greenland, and the birth place criterion became a symbol and tangible proof of the fact that Greenlanders did not have political equality with Danes (Janussen 1995). Meanwhile, Greenlandic language and culture were increasingly neglected. As this became more evident, Greenlanders began to demand ‘Greenlandification’ rather than Danification (cf. Sørensen 1995: 101). This was officially declared to the Danish government in 1972, leading to Home Rule in 1979, but it was not until the early 1990s that the remaining privileges from birth place criterion were revoked (Janussen 1995).

In 1973, when Greenlanders began to demand changes in the political strategy of the post-war period, the band Sume (‘Where?’) released their first album “Sumut” (‘Where to?’). The album was produced and released by Demos, a socialist and anti-imperialistic publishing company in Denmark founded by the Danish Vietnam Committees. The record company behind the release was thus an explicitly political one, and their interest in releasing this music was sparked because the lyrics were in a native language and criticized Danish imperialism (Lynge 1981: 64). This political backdrop probably had the effect of strengthening the political messages in the band’s material.

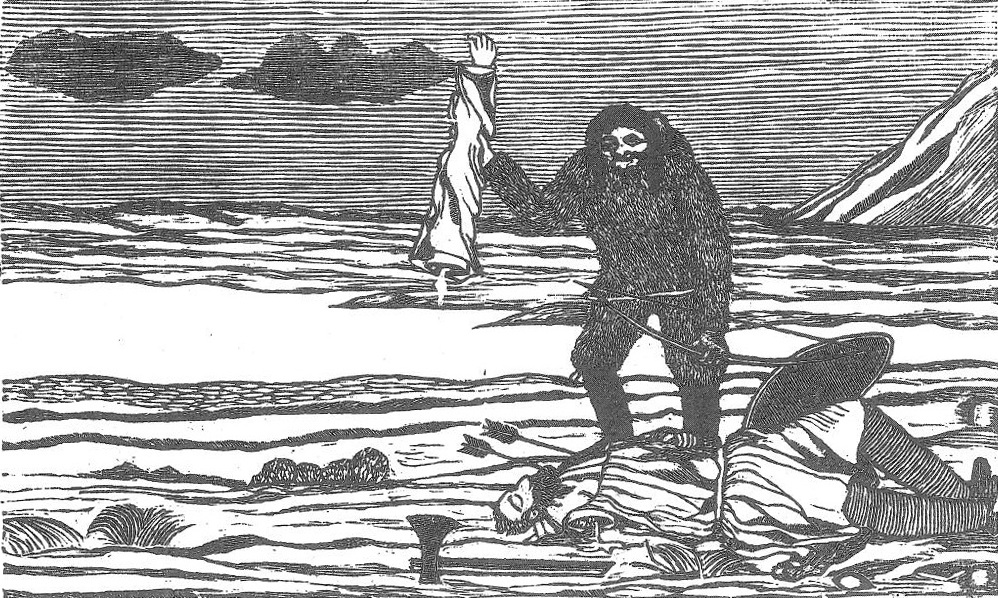

The lyrics featured in Sume’s music were primarily concerned with topics from a Greenlandic context, and the lyrics made use of figurative language and metaphor to express demands for independence and cultural awakening in Greenland. The lyrics bear witness to a time when Danification was viewed as an eminent threat to Greenlandic identity and the population’s right to sustain their distinct culture (cf. Langgård 1990: 24, 28-30; Berthelsen 2010: 16; Langgård 2013: 81). Sume’s first album cover gave further voice to their opposition to Danish influence in Greenland. The cover is a copy of a woodcut made by the artist Aron of Kangeq in 1860 that depicts a scene from Greenlandic myth in which the legendary figure Qasapi has just cut the arm of the dead body of the Norsemen chief Uunngortoq (see fig. 1).[i] The cover of “Sumut” could thus be interpreted as an appeal to take up armed resistance against Danish influence in Greenland. However, despite differences in opinion and a sometimes harsh atmosphere in public debate, armed conflict has never seemed to be on the agenda of the colonized nor the colonizers in Greenland, and the cover of “Sumut” should probably only be read as a provocation.

Sume’s music had an enormous impact on Greenlandic popular music. “Sumut” was the first Greenlandic rock music featuring Greenlandic lyrics ever to be released. It became very popular in Greenland, and even amongst the Danish left, and played an important role in reviving Greenlandic as a complex and autonomous language (Henriette Rasmussen quoted in Langgård 2004: 103-4). This had deep repercussions in the music scene in Greenland in the years that followed. Up to the mid-1990s, almost all the music released in Greenland featured Greenlandic lyrics. With Sume, Greenlandic popular music became, and remains, a forum in which the Greenlandic language is strengthened and evolved through creative use. This trend began with Sume’s first album “Sumut”, which became a pioneering record because it set the stage for a particular form of Greenlandification of popular music.

This Greenlandification of popular music was achieved by performing a sense of place, mainly by use of the Greenlandic language and through the themes found in the lyrics, but Sume also used other elements to connect their music with a Greenlandic place. Several tracks on the band’s first album included wordings such as ‘Aajai ja aai aajaa aa’, that, as already mentioned, can be traced back to pre-colonial songs, but Sume was the first to introduce into rock music another kind of performance of place. On the band’s third album released in 1976, the sound of a frame drum performance was incorporated into one of their recordings. In the intro of the song “Kalaaliuvunga” (‘I am a Greenlander’), Egon Sikivat’s (1941-2009) voice accompanied by the frame drum, is heard for about one minute before Sume enters the soundscape with their 1970s rock sound. The sound of Sikivat’s performance however re-emerges regularly in the soundscape throughout the song, and as the rock music fades to the background by the end of the track, it is once again just the singing and the frame drum that fill the soundscape, but this time the band does backing vocals for Sikivat’s performance. Since this epic release, introducing elements from the frame drum dance and song tradition into popular music in various ways has become a common method for performing a sense of Greenlandic place in global musical forms such as rock, pop and rap. The sound of the frame drum tradition has become an audible symbol of Greenlandic identity in popular music, and Sume was the first to introduce this trend.

Sume’s third album, featuring the track “Kalaaliuvunga”, was also the first album to be released on the label ULO, the first professional Greenlandic record company, which was set up on the initiative of one of the band’s lead singers Malik Høegh, the band’s drummer Hjalmar Dahl and Karsten Sommer, the band’s producer from their former productions with Demos. In the years that followed, ULO dominated the Greenlandic record market by releasing some of the most epic albums in Greenlandic popular music history, but in 2004 the record company closed down their studio following a period in which their productions had resulted in deficits (Andersen and Otte 2010: 61). The company is however still occasionally active today.

In 1980 the other lead singer from Sume, Per Berthelsen, started up his own record company in Nuuk called Qilaat-music. In the years that followed, Qilaat-music released several popular albums like those made by Per Berthelsen and his younger sister Birthe Olsen, whom he had recorded with prior to the setting up of Qilaat-music. However, when Birthe Olsen died from cancer in 1987, Per Berthelsen gave up his musical activities for a while and sold Qilaat-music to Eigil Petersen, the lead singer in the popular rock band G-60 (Interview with Per Berthelsen, 30 April 2011). Eigil Petersen changed the name of the label to Sermit Records, which was changed again later to Ice Music owned by Eigil Petersen and Alex Andersen. Alex Andersen took over Ice Music in 2009, and the company was closed down in 2012 as the result of a general crisis in the music industry in Greenland.

Members from the band Sume thus had a tremendous impact on the Greenlandic popular music scene, not only because they were the first band to present rock music in a Greenlandificated form that is still very much used, but also because several of the band members played important roles in setting up a music industry in Greenland that made it possible to record, release and distribute music in LP format in the country.

Fig. 7: ”Inuit Nunaat” (‘The land of people’) by Sume (1974).

[i] The Norsemen where a population of Vikings that immigrated to Greenland from Iceland and colonized parts of the south and west coast around the first millennium, but disappeared about 500 years later (Sørensen 1995: 86).